Six Northern Ontario First Nations are challenging the province’s Mining Act in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, arguing it is unconstitutional and overrides their treaty and Charter equality rights.

The leaders of Apitipi Anicinapek Nation, Aroland First Nation, Attawapiskat First Nation, Fort Albany First Nation, Ginoogaming First Nation, Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug filed a notice of application with the court on Aug. 9.

They take issue with Ontario’s long-tenured free entry system and its digital claimstaking process, which allows companies and mining interests anywhere in the world to stake prospective mineral exploration ground with a mouse click.

Indigenous leaders argue this is happening on their traditional land without the required prior engagement with First Nations. They say the Mining Act regime automatically registers exploration ground, allowing claimholders certain land rights that trump First Nation constitutionally protected rights to their lands.

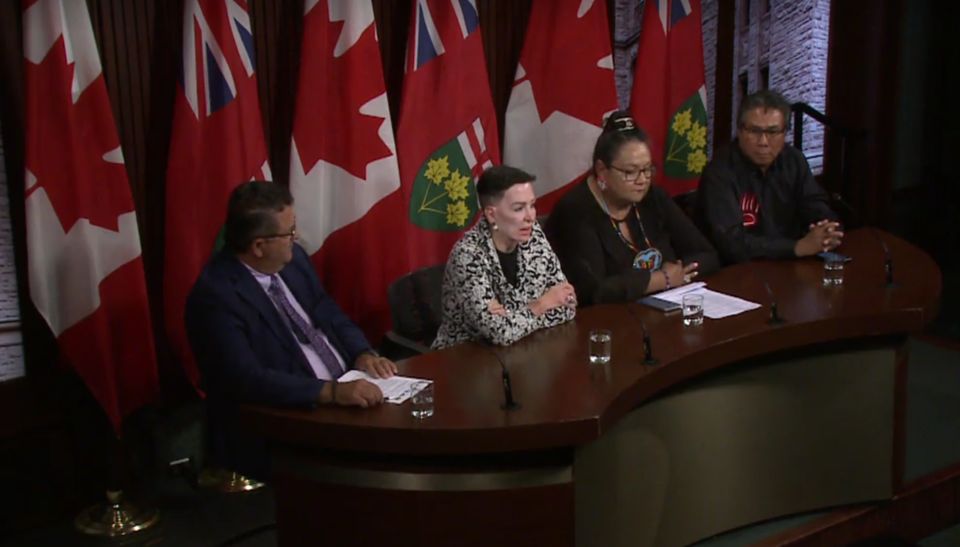

At an Aug. 12 Queen’s Park press conference, Kate Kempton, lead counsel, called the Mining Act “racist and colonial” and said “it must fall.”

The communities want certain provisions of the Mining Act declared unconstitutional, struck down and replaced.

They also point to an “abysmal system of consultation” about exploration on claims and their inability to protect their lands.

A response from Ontario's Ministry of the Attorney General was not available at the time of this posting.

Northern Ontario is in the midst of an exploration boom, particularly in the search for critical minerals like nickel, copper and lithium.

The First Nation leaders contend dozens of claims daily are being staked on their traditional territories without their knowledge until after the claims are registered. Kempton called the government’s consultation process “nothing more than a paper chase” that involves sending out form letters to First Nations.

“It’s an appalling, insulting and discriminatory regime,” Kempton said, that does nothing to protect the rights and interests of First Nations.

There are 2,000 active claims in Ontario in the Mining Lands Administration System.

By way of on-the-ground impact, the chiefs said these claims on their traditional lands prevent expansion of their reserves, prevent the creation of parks, are impeding their way of life, and prevent them from being “stewards over our lands as our laws tell us we must."

Kempton said the Ford government’s push for critical minerals extraction to supply the electric vehicle manufacturing economy has opened up a level of staking activity that is “over-the-top-ridiculous."

In Ontario, mineral exploration activity is regulated under the Mines Act. Under this act and through digital claimstaking, prospectors and exploration companies can register mineral claims on unclaimed Crown lands and conduct exploration.

Apitipi Anicinapek Nation Chief June Black called the Act a “racist” piece of legislation that automatically “bulldozes” Indigenous and property land rights to 95 per cent of the province.

“This is a free-for-all, virtually,” said Black. “No restrictions, claims are automatic.

“The system of consultation is so weak as to be non-existent.”

The Mining Act has been amended over the years following challenges and ugly incidents involving Kitchennuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation (KI), junior miner Platinex in northwestern Ontario, and Wahgoshig First Nation (now Apitipi Anicinapek) against explorer Solid Gold Mining.

In challenging the system, Jacob Ostaman, KI’s land and environment director, reminded all that their leadership were jailed in 2008 for opposing, what they viewed as, “unlawful incursion” on the traditional territory that went against their rights of holding ultimate decision-making power over their lands.

“It is our sacred duty to protect land as entrusted by our ancestors.”

Some precedent in this area was established last September when the B.C. Supreme Court ruled that automatically granting mineral rights without consultation with First Nation communities is unconstitutional.

Grassy Narrows First Nation already got a head start last month by issuing a notice of application in the Superior Court of Justice, arguing the lack of adequate government consultation breaches their constitutionally protected treaty rights.

When Kempton was asked by Northern Ontario Business if there is a possibility that their challenge could be joined with Grassy Narrows, she responded by email: “It is possible that we might collaborate or have the cases run back to back, but it is too early to know.”

As to a legal action timeline, Kempton is hopeful of seeing a decision delivered within a year to 18 months.

She said bringing a notice of application forward, to argue the application of the law and not the facts, is faster and more cost-effective than a formal lawsuit, which could last seven to 10 years before a decision is reached.