When talking about protecting vulnerable communities amid the COVID-19 pandemic, groups often discussed include the elderly and those with compromised immune systems. One population often overlooked is Indigenous peoples in Canada, especially those living on reserves.

Though navigating through unprecedented circumstances, the government must prioritize the health and safety of Indigenous communities and create collaborative policies specifically tailored to meet their unique needs and circumstances.

Often enough, what works for the rest of Canada does not work for Indigenous peoples. For example, the universality of the Canada Health Act’s purpose is to ensure health care provision follows uniform terms and conditions, supposedly providing the same quality of service throughout Canada. As many Indigenous communities can attest to, this is often not the case; there is a well-being gap between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Canadians.

If Canada can step up to the plate and curtail this crisis in Indigenous communities, their actions could perhaps open the door to further cooperation and reconciliation efforts in the future.

But first, the government must prove itself through the quick deployment of adequate social programs and policies to help Indigenous communities when they need it the most.

The vulnerability of Indigenous communities

Indigenous communities, especially the ninety-eight remote fly-in-fly-out areas, are particularly vulnerable to a pandemic. Inuit in the North are already more susceptible to respiratory illness from overcrowded housing, poverty, and food insecurity. Moreover, they also rely on outside jurisdictions, mainly urban centres, for most health services.

Overcrowded housing undermines conventional physical distancing measures, like staying at home, that are recommended by Canada’s public health officials. The ability to isolate or social distance hinges on access to stable and adequate housing, something the government must prioritize providing. In addition, frequent hand washing presumes that one has access to clean water.

In fact, 61 Indigenous communities in Canada are still under a “do not consume” or “boil water” advisory, meaning residents must use bottled water to wash their hands; 13 of these communities are in Northern Ontario. Indigenous communities need to have the capacity to follow all recommendations set out by public health officials; many currently do not.

The gaps in pre-existing social programs

Due to the federalist nature of Canadian politics, policies pertaining to the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples fall between both federal and provincial jurisdictions. This convoluted relationship between different levels of government does not go away during a pandemic; in fact, the strains in the provision of health services are amplified.

Indigenous peoples have historically fallen victim to these jurisdictional loopholes; the multiple layers of government, though useful in some situations, results in weak accountability and oversight pertaining to Indigenous issues.

While the provinces are responsible for most social programs in Canada, the federal government handles relationships with Indigenous peoples as well as treaty negotiations.

As Martin Papillion, Director of the Centre de recherche sur les politiques et le développment social, acknowledges, both levels of government attempt to “divest” from their responsibilities to Indigenous peoples, whether that be for financial, political, or social reasons. This political shit-show leaves virtually no room for Indigenous communities to be involved in the policy-making process, leaving Indigenous peoples with the lowest quality of service available.

The Canadian Constitution divides responsibilities up between the provincial and federal governments in a way that is not currently conducive to Indigenous well-being and reconciliation.

Is $305 million enough?

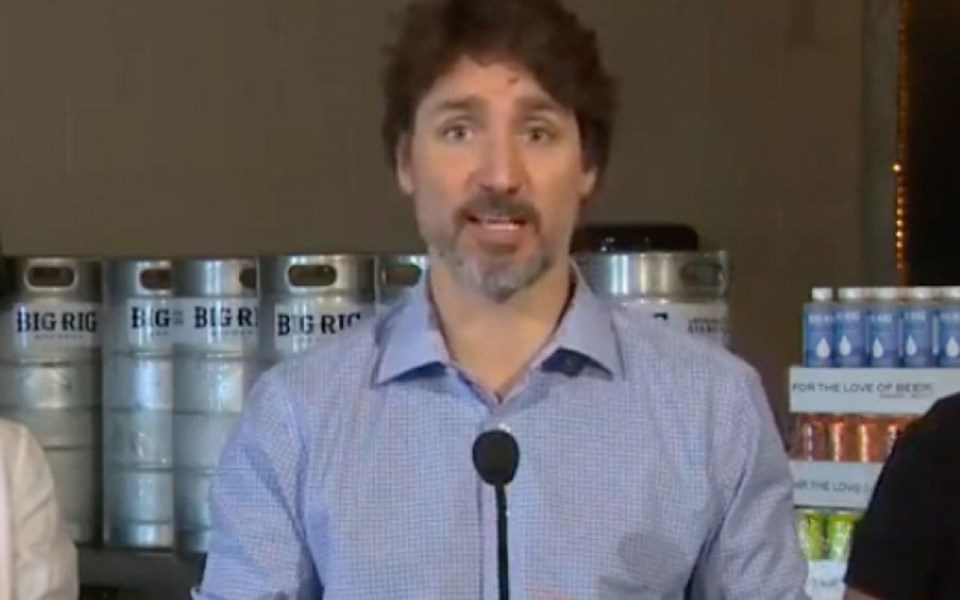

On March 18, the Trudeau government took the first step in the right direction by announcing a $305 million Indigenous community support fund. The money will be allocated to COVID-19-related expenses ranging from purchasing supplies, such as hand sanitizers and masks, to covering travel expenses and repurposing community buildings for medical care, isolation sites, and storage space.

But, is this money enough? In late March, the Assembly of First Nations declared a state of emergency for its First Nations, stating that the money Ottawa has committed to date will not go far enough to meet the unique needs of the Indigenous populations facing this pandemic. It is justified for these communities to be wary of governmental assistance provided historical colonialism and ambiguity around the implementation of new policies.

The stimulus package was meant to cover the “immediate needs” of Inuit, Metis, and First Nations communities. However, this package only came into effect in May, months after the virus landed in Canada. Indigenous communities were left with little-to-no governmental assistance during the critical early stages of the pandemic.

One thing does remain certain: the sooner the response, the better. The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Indigenous communities remains low, but it is rising, making quick action necessary to prevent the spread as soon as possible.

Comprehensive social policies, now more than ever, have the potential to save hundreds of lives. Indigenous communities need more than just a blank cheque right now - they need medical professionals, hand sanitizer and clean water, and less crowded housing.

Months later, the federal government announced additional measures to help curb the spread of COVID-19 in Indigenous communities. Some supports include additional funding for Indigenous businesses and tourism, a community support fund, and interest payment relief.

Moving forward

Indigenous communities need an active, continuous commitment; they must be involved in federal and provincial decisions that are disproportionately negatively affecting their communities. The current pandemic is putting the future well-being of Indigenous generations at risk, and this risk will not disappear when the threat of COVID-19 is gone.

What is crucial to remember is that the fundamental problems plaguing Indigenous communities will not cease to exist following the end of the pandemic. Once the COVID-19 package runs out, Indigenous communities will still be left with overcrowded housing, inadequate access to health care, and many will still not have clean drinking water.

In order to allow the reconciliation process to continue, Indigenous-driven social policies must be enacted for the long-term.

A history of mistreatment by the Canadian state will take decades to reverse, if that end goal is even possible. Though these efforts might start with the government’s response to COVID-19, the efforts must not end here.

Author: Mercedes Labelle is a Research Analyst at NPI.