When I retired from the Ministry of Natural Resources (now “and Forests”) in 2000, it had, in my opinion, the best moose management program in North America. Unfortunately, managers did not practice “adaptive management” and the program failed to produce the expected increase in the moose population.

Adaptive management simply means that you use the best information available to make a plan and if it doesn’t produce results, you change what you are doing until they do.

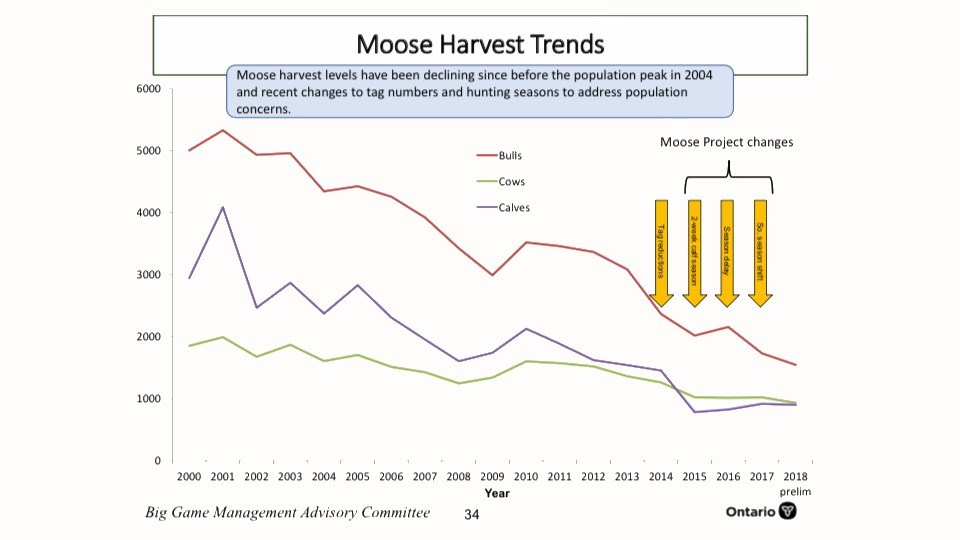

MNR had the first glimmer that things weren’t working properly in the early 1990s, but the information system had problems. These were cleaned up and by 2000, there was unequivocal evidence that the population was being mismanaged by MNR itself.

More than 60 per cent of actual harvests exceeded those planned (1).

In spite of that knowledge, my sources tell me this pattern continued. It should be no surprise then that the population continues to decline after 35 years of “selective harvest”. In the 2019 review, over-harvest was not even identified as a possible — yet probably the most significant — cause of the decline.(2)

With adaptive management, the number of tags should have been reduced until the kill equalled the planned harvest. Once that occurred, MNRF would be in a position to determine if harvest planning guidelines were effective. Neither of these things happened.

In essence, the numbers of tags have never regulated the kill over most of the province. The kill depended on how many moose were vulnerable and exposed to gunfire or arrows.

In 2014, I wrote a critical paper on the program (3). It was based on my experience compiling all existing moose data and creating the information sets needed and used to manage moose effectively. It was provided to the MNR, the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters, and others. You can read it here.

When one criticizes, it is incumbent that one offers a “better” alternative. That I did.

This year, the MNR implemented about 99 per cent of that proposal (Ref. 4, pg. 58). Initially, I felt very positive and hopeful that real change was happening. As soon as I saw the tag allocations (5), I knew that my hopes were false and the program, at least in its infancy, was doomed to fail.

The previous management system only controlled the harvest of bulls and cows. That was the theory, and if used properly, it would have worked, but it never happened. Any hunter could get a calf license and “party hunting” rules permitted them to kill adults if tags were held by others in the group. The logic that prevented changing that system was that if calf harvest was limited, then many people wouldn’t be able to hunt.

The proposal solved that problem. The fundamental principle behind the alternative was that one tag would be issued for each animal to be harvested and as many people could participate as desired. This provides absolutely direct and accurate control of the kill. It also emulates the highly successful programs used to restore moose in Fennoscandia. (6, 7)

It has been my experience that when a proposed program change is accepted for implementation, it ends up in a committee that has little understanding of the program. They often make changes without consulting the “architect” and the changes invariably result in problems.

Such is the case with new program. The one-tag principle was ignored and nearly 17,000 tags are being offered. That means that there is a potential to kill 17,000 moose by more than 90,000 annual hunters. This would be as high as the kill during the “best” years of hunting. The permitted kill of adults by guns is nearly 9,000 moose. (5).

A sustainable harvest is probably close to five per cent at current population levels — meaning a total harvest around 4,500 moose from a population of 90,000. The current recommended harvest for population growth is four per cent, so the allowable kill must be even lower at about 3,600 moose (8).

Obviously, there is no true control over the harvest and again it will be dictated by the number of vulnerable moose. For this reason alone, the program is doomed to fail. Seventeen thousand moose will not be killed because there aren’t that many that are vulnerable, but there is nothing to prevent the kill from exceeding 3,600 or 4,500.

Whether the managers learn from this and apply adaptive management adjustments is to be seen. Based on past practice, I’m sceptical. If they can’t get the foundation right, I doubt they understand enough to fix any future problems.

There are other failures in the harvest aspect of the program. Based on gun tags alone, if they are following the one tag principle, the minister’s advisory committee, composed only of hunters and outfitters (9), is allowing the killing of more cows than bulls. Apparently this is being done to “balance” the sex ratio in the herd. Are there really too many cows for bulls to service? Is killing more cows really going to help the population grow when cows are key to growth?

Big game management is similar to cattle farming. You protect your breeding stock, especially the females, and “remove” the younger animals. With polygamous species, you can have considerably fewer males as long as there is no problem with “access” to the females — which might be expected at low population densities.

The logic of killing the most important breeding animals especially in a declining population and where there is concern about the scarcity of calves, totally escapes me. In my opinion, the exact opposite is required — don’t kill more cows but protect more bulls.

Moose are long-lived and it would only take a few years of reduced bull harvest to restore the balance, if, in fact, that is the intent. Regardless, protecting should be the primary objective. It would be prudent to prohibit the killing of cows until the herd has started to recover. Protection of cows is a fundamental component of the hunting system’s in Fennoscandia (6, 7).

Both of these measures will upset many hunters, but their demands have brought the herd to the point that drastic measures are required and they need to accept that responsibility.

Providing 3,600 killing opportunities to more than 100,000 licensed hunters (Ref. 2, pg 24, for more hunters than moose, 8) will certainly mean that many parties will not be able to hunt until the herd rebuilds.

The alternative is continued over-harvest until the herd is seriously threatened and there is no hunting for anyone.

There is a fact of life that when you mismanage or squander what you have, there comes a time of reckoning. If the decline is not stopped, it may get to a point where it will not recover without drastic action, including complete season closures for many years.

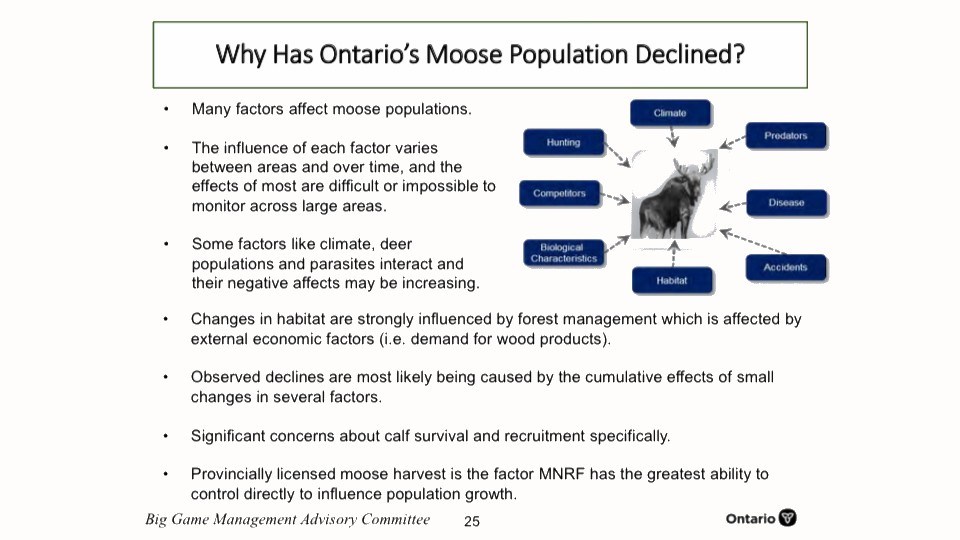

While the “Moose Management Review” of 2019 (Ref. 2, p 25) did not identify over-harvest, it did acknowledge that through “licensed moose harvest is the factor MNR has the greatest ability to control directly to influence population growth.”

The review and recommendations stemming from it were designed around what hunters want, not what is required to protect the population. Clearly, they are not controlling the licensed harvest effectively. Moose are being managed by hunting interests for hunting interests with little apparent concern for the future of the herd or the interests of other Ontario residents.

The second major failure is that the minister has not included First Nations in the management process. If MNR manages to stop population decline, unregulated subsistence hunting could impact and stall recovery in many units.

There seems to be an expectation that if MNR staff “engage with First Nation’s communities,” they will regulate their harvest and leave more moose for sport hunters to kill.

Perhaps it’s because I was a dumb public servant, but that sure doesn’t make sense to me. I certainly wouldn’t co-operate with those who treat me as a second-class person, shut me out of decision-making and expect me to give up my treaty rights just for the benefit of those who have no respect for me.

What is required is inclusion and negotiated allocations to subsistence and recreational hunting, along with protocols to ensure proper management. I estimate that there is potential for a moose population in the range of 300,000 to 400,000 moose with decent habitat, effective harvest control and perhaps managed predator control when necessary, and MNR is proven capable of regulating it (3). Everyone would benefit immeasurably.

Greg Rickford, the current MNRF minister, is interested, I understand, and capable of addressing the problems with moose management. I sincerely hope this is true.

By the same token, non-hunters have also been excluded as advisers to the minister, even though resources are held in trust for all residents of the province. Again, the wisdom of leaving the solution for over-hunting in the hands of hunters escapes me. It has failed for the past 35 years. Why should anyone think it will work now?

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both Internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London , Ontario.

References

1: 1999 and 2000 Moose Harvest in Ontario. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Northwest Science and Information Technical Report TR-131.

2: Moose Management Review, 2019. Big Game Management Committee, https://www.ofah.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/MMR-engagement-presentation-May182019-compressed-002.pdf.

3: Moose Management in Ontario: An Alternative Strategy. 2014. A. R. Bisset. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/Moose-alternative. Click on text to open document.

4: Ontario Hunting Regulations, https://files.ontario.ca/books/mnrf-2021-hunting-regulations-summary-en-2021-04-01-v2.pdf.

5: Moose tag quotas. The original tag allocation has been replaced by the tags available for the second draw, https://www.ontario.ca/page/moose-tag-quotas.

6: A Comparison of Moose Management between Alaska and Scandinavia. 2011. S. Brainerd and D. James. Sportsman’s Voice, http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/home/library/pdfs/wildlife/research_pdfs/comparison_moose_management_scandinavia_alaska.pdf

7: Status of the Moose Population and Challenges of Managing Moose in Fennoscandia. 2003. S. Lasvund, T. Nygren and E. J. Solberg. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tuire-Nygren/publication/274379611_Status_of_moose_populations_and_challenges_to_moose_management_in_Fennoscandia/links/551d314b0cf2000f8f9387be/Status-of-moose-populations-and-challenges-to-moose-management-in-

8: The current recommended harvest is four per cent for population growth. Personal communication with Phillip DeWitt, Provincial Wildlife Monitoring Program Leader, MNR.

9: Members of Minister’s Big Game Management Advisory Committee, https://www.pas.gov.on.ca/Home/AgencyBios/569?appointmentId=9195