Salary caps are a controversial issue in any collective bargaining situation in professional sports. The introduction of a cap by National Hockey League owners resulted in a lockout that led to the cancellation of 2004-05 NHL season. The salary cap issue caused another season disruption in 2012-13.

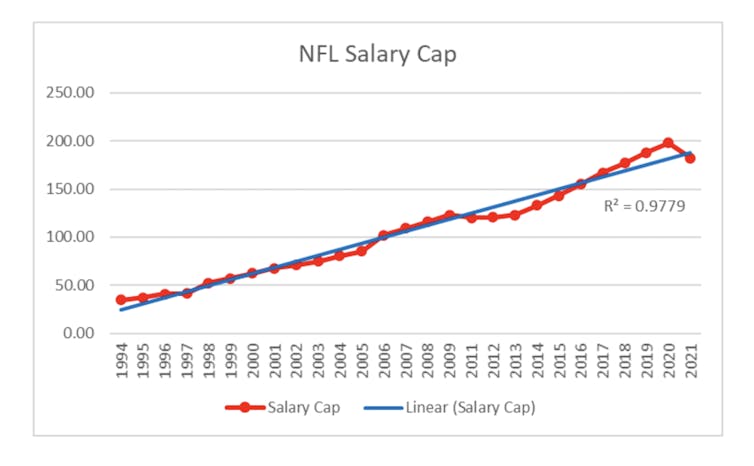

In short, salary caps limit the amount of money a professional sports team can spend on their athletes. The National Football League was the first professional league to introduce one in 1994, followed by the national basketball and hockey leagues in later years.

The reason the NFL salary cap came into place was to make the league more competitive and to avoid runaway payroll spending by wealthier teams, in contrast with Major League Baseball (the only North American sports league that doesn’t have a salary cap) that has teams of “haves” and “have nots” because of asymmetric payrolls.

To make the league more competitive — and avoid having differences in the performance of large and small markets teams — the NFL also employs revenue sharing. Both these mechanisms make the NFL one of the most socialistic professional leagues around the world, where teams share about 60 per cent of the league’s revenues. Without revenue sharing and salary caps, it would be impossible for small market teams like Green Bay or Buffalo to compete.

The NFL cap is characterized as a “hard” one because teams must always stay under it, but there are still ways around it. The NFL also introduced a hard salary floor — a requirement that all teams spend at least a certain percentage of the league cap. Both the cap and floor are tied to the league’s revenues and are adjusted annually. Until the last two collective bargaining agreements, the salary cap was at 50 per cent of the NFL revenues.

Due to contractual issues, there was no salary cap in 2010, leading to a long lockdown in 2011, followed by a settlement between the NFL Players Association and the NFL collective bargaining agreement that reduced the salary cap from 50 per cent of the revenue to 47 per cent. This led to the flattening of the salary cap.

Because of COVID-19, the league’s revenue dropped even further in 2020 and hence the 2021 salary cap will drop from $198 million to $182.5 million.

Manipulating the salary cap

Salary caps can be manipulated by allocating some of the contract to a signing bonus, which, in turn, is distributed over the years of the contract. However, this strategy can result in “dead money” counting towards the salary cap if a player leaves the team. Quarterback Jared Goff’s contract with the Los Angeles Rams is an example of this.

In 2019, the Rams signed Goff for a five-year contract extension, with a signing bonus of US$25 million (counting for US$5 million per year towards the salary cap).

Last year, Goff renegotiated his contract and received another US$9 million signing bonus. This combined signing bonus was prorated for an annual US$6.8 million for 2021, 2022 and 2023 and $1.8 million in 2024.

However, the Rams traded Goff to the Detroit Lions and even though Goff is no longer with the team, the Rams will have to count the signing bonus ($22.2 million in total) towards the salary cap for the next four years.

The cryptocurrency loophole

A novel and fascinating way to circumvent salary caps is illustrated by the recent use of cryptocurrency fan tokens by Paris Saint-Germain as a signing bonus of Lionel Messi, one of the most iconic soccer stars in the world.

Paris Saint-Germain-issued fan tokens are linked to Ethereum (a cryptocurrency) and allow fans to participate in some decisions made by the team (for example, the music used by the team or armbands worn by the team) and connect socially with players. These fan tokens can be traded and their price is related to the team performance.

It is estimated that the fan tokens granted to Messi by Paris Saint-Germain are valued between 25 million and 30 million euros. One advantage of fan tokens is that they are cheap for the issuing team, but provide real value to the recipient. The biggest advantage is fan tokens are not considered for salary caps (which are called “financial fair play” rules in European football).

The Messi situation likely means two things are happening now in other professional leagues: franchises are investigating using the same crypto tool to circumvent salary caps and leagues are considering ways to close the loophole. Ironically, rich teams in North American pro leagues (the Yankees, the Dodgers, the Lakers) that might issue fan tokens will become even richer because they have the biggest following of fans.

The effect of salary caps on players’ salaries

I’m a professor in financial analysis and in my day job, one of my areas of research is how game theory is applied to financial situations. Game theory is the study of strategic interaction among players (individuals or firms) to explain their behaviours. Businesses, sport teams, military organizations and governmental policy makers commonly use it on a regular basis for strategic decision making.

From a game-theoretic viewpoint, major league sports should be characterized as an “all pay auction,” where every bidder pays the bidding costs but only the winner takes the prize. This type of analysis leads to an interesting and unexpected insight — salary caps increase the payroll spending of teams.

Without salary caps, the “have not” teams might feel like they have no real chances against the “haves.” But because of salary caps, these teams do feel like they have a fighting chance, so they spend money on player salaries, which increases the average team payroll spending. This means the immediate effect of a salary cap is an increase in the average player’s salary, while superstars’ salaries decrease. From this perspective, the NHL Players Association’s early war against the salary cap ended up hurting average players and protecting the superstars.

The other effect of a salary cap is that having a more competitive league helps teams grow their fan bases (because no one wants to watch a team that always loses, although the Toronto Maple Leafs are an exception to that rule). That, in turn, can increase the league’s revenues, leading to a higher cap and, ultimately, higher salaries.

To show this, I analyzed the average team payroll in the NHL since the introduction of the salary cap. As the chart below shows, the average team payroll has been trending upwards in the NHL since the establishment of the salary cap, not counting the lockdown year.

Salary caps have been around since 1994 and are used in all North American professional sport leagues with different degrees. They were instituted to enhance competitiveness among league teams, and to large extent were successful in achieving this goal.

Despite the opposition of salary caps by player unions in the past, game theory and actual data shows that caps have actually increased average players’ salaries over time. Coupled with how salary caps can help smaller teams stay competitive against those with deeper coffers, it’s clear they currently play an important role in the financial well-being of major league sports teams.![]()

Ramy Elitzur, Associate Professor, Financial Analysis, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.